Note: There is a short version and a long version

I am beginning a second “book” project that focuses on Mexican visual culture of death and dying from c. 1521–c. 1920, from the arrival of Spaniards into the city of Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City) in 1519 to the end of the Mexican Revolution in 1920 and its immediate aftermath.. Some of the most popular and prevalent images we associate with Mexico are of skeletons and skulls, realized in the works of artists like José Guadalupe Posada, in Day of the Dead paper-maîche figurines, and in Aztec skull racks and cadaverous masks. Given the myriad visual objects from Mexico that seem to communicate a fascination or fixation with death and dying, it seems appropriate that anthropologist Claudio Lomnitz asks with respect to Mexico, “Can Death be a national symbol?” [1]

I think digital art history will help me gather and analyze data in new ways, as well as allow me to share some of my research in a public forum. My hope is that this project will connect me to others working on related topics and generate discussion about a topic that receives a lot of popular attention.

[If you are reposting this, feel free to end here!]

More about the project goals, questions, ideas

My project takes a broad approach to consider the long history of Mexico’s changing relationship with death and dying. Bracketing my study between 1519 and c. 1920 allows me to present an overview of Mexican visual culture focused on death and dying, as well as to discuss shifting social concerns, political regimes, artistic media, and religious practices over several hundred years that affected Mexican deathways. Moreover, by bookending my project within this 400-year period, I can examine the transformations in deathways in eras marked by high numbers of deaths, whether due to illnesses, social upheavals, warfare, or infant mortality issues. Some important questions guiding my project include: What changes occurred from the time indigenous artists produced images of epidemic victims in the Codex Telleriano-Remensis (mid-16th c.) to Francisco Goitia’s Landscape of Zacatecas (1912) in which a decaying body sways from a tree branch in the dry, desolate Zacatecan landscape? In what ways can individuals use death-related objects, like portraits of deceased family members, to increase their social and political positions? How do eighteenth-century painted portraits of dead elites produce meaning differently than mid-to-late nineteenth-century photographs of the dead? Do artworks demonstrate a democratization of death in Mexico between 1519 and c. 1920? How does the veneration of saints’ body parts and bodily effluvia differ from that of the body and blood of war heroes?

Mexican visual culture in this 400-year time span has numerous examples of death-related objects, images, monuments, and performances. However, art historians tend to ignore them, for reasons ranging from aesthetic considerations to morbidity, or to focus on them in only the most general fashion. Several art-historical studies serve as important inspirations for my project, especially Beatriz de la Fuente and Louise Noelle’s edited volume on funerary arts in Mexico and Nigel Llewellyn’s book on the art of death in early modern England.[2] My approach is inherently interdisciplinary, drawing on more traditional art-historical methods such as style, iconography, and social history, as well as ideas in anthropology, psychology, philosophy, and the history of science. In particular, scholars in history and anthropology—including Claudio Lomnitz, Philippe Ariès, Martina Will de Chaparro, Miruna Achim, and Stanley Brandes—have considered aspects of Mexican deathways. My project builds on their important work, but focuses primarily on visual culture as a way to access past concerns about life and to understand how images and objects actively produced meaning for people.[3] I see my project as a useful way to enter into larger scholarly conversations about death, dying, and the afterlife, as well as adding a more nuanced view of Mexicans’ relationship to death over this expanse of time. Some of the main themes of my project include arts that aid people in times of sickness, such as the epidemics of the first Great Dying; arts created in response to millenarian concerns, or the end of days; arts used to obtain a “Good Death”; the display of relics, corpses, and death portraiture; sacrifice, nationalism, and martyrs in the post-Independence period; capturing the dead in photographs; and artistic responses to or documentary photos of the Mexican Revolution.

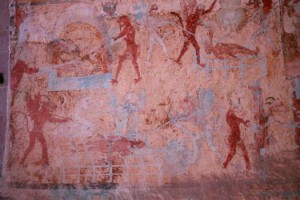

Here, I would like to expand on some of the themes and ideas guiding this project as a way to demonstrate its importance for understanding one facet of Mexican culture and its relevance to discussions about death and dying more generally. Over the course of Mexico’s colonial period, from 1519-1821, objects, texts, and performances speak to the significance of death in the lives of those living in the Spanish colony. The first Great Dying that begins this project occurred between the years 1519 and 1595. It is estimated that the indigenous population of Mexico declined by approximately 65-95%, resulting in the death of millions of individuals. With over 10 million people, the population was reduced to a mere 1-2 million, the result of epidemics, famine, violence, and reorganized labor that caused this major demographic catastrophe in the wake of Spanish colonization. The pervasiveness of death baffled Spaniards and Indigenous alike, with each theorizing as to why the dead outnumbered the living. One way to navigate the horrific tides of death was via visual culture. Manuscript drawings, mural cycles, theatrical performances, and sculptures convey the constant anxieties about death and the afterlife. From the evidence I have gathered thus far, it seems there were conflicting views about death and the afterlife during this era, and my goal is to probe these alternative viewpoints as a way to gain entry to the past.

After the first Great Dying, objects began to advertise different concerns about death and the afterlife, particularly concerns over how to live in order to achieve a good death (“la buena muerte”). While we might be more accustomed to the medicalized approach to death in westernized culture, the population of colonial Mexico was more accustomed to death in their daily lives. In fact, the colonial art of death and dying speaks mainly to the living: often the concern is how the dead can improve the vitality of a still living family or person, or model for someone how to gain entry to a heavenly paradise. Numerous paintings depict souls burning in Purgatory or martyrs spewing blood from wounds. Processional sculptures showcase the flagellated back of Christ—with some even incorporating actual human bone into them—and ornate vessels contain the miraculously preserved bodies or body parts of the dead. Vanitas symbols grace paintings, sculptures, and buildings. Horrifying scenes of hell remind people of what awaits them if they live improperly, and images of rotting bodies realistically portray the process of decay. Even types of jewelry contained bits of bone, flesh, and blood—a testament to the desire to keep the dead near to one’s body. I am particularly interested in how different individuals or groups of people harnessed deathways to increase one’s political power, social standing, financial gain, religious standing, and even nationalistic fervor. To provide but one example, numerous indigenous communities in the eighteenth century commissioned sumptuous altarpieces depicting souls burning in Purgatory, and they often included portraits of community members among those enflamed. Moreover, altarpieces showing ritual feasting or celebrations of dead community members are often paired with depictions of Purgatory. Altarpieces like these not only aided people in their spiritual life, but also connected them to lived communal experiences—or so I hypothesize at this time.

The century after Mexico achieved independence from Spain (1821) is marked by civil strife, more foreign incursions, continued health issues, and nationalistic concerns. In the mid-nineteenth century, for example, artists working for the Royal Academy of San Carlos began to look to the Mexican past to assist in the formation of a new Mexican identity. Rather than depict subjects drawn from the Graeco-Roman past or even contemporary Europe, artists painted or sculpted bloody scenes of the Spanish Conquest as one way to excite national pride. Outside of academic art, the introduction of photography in the nineteenth century had profound implications for capturing death practices or creating works about death. Two different phenomenon are of particular interest to me: the photographic narratives surrounding the execution of Emperor Maximilian and photographs of dead children dressed as saints and angels. While each phenomenon speaks to different types of socio-political concerns in the nineteenth century, they both tackle loss and tragedy.

- Angelito Photography

The second period of Great Dying serves as the closing bracket for my project. Beginning in 1910, the Mexican Revolution cost millions of lives. According to Robert McCaa, “From a millennial perspective, the human cost of the Mexican Revolution was exceeded only by the devastation of Christian conquest, colonization, and accompanying epidemics, nearly four centuries earlier.”[4] The effects of this massive dying resulted in a bevy of artistic responses, whether created during the violent decade or shortly thereafter in the 1920s and 30s. While many people today recognize José Guadalupe Posada’s Day of the Dead broadside prints, fewer people know his gritty prints documenting the Revolution. Francisco Goitia experienced battle, and so had first-hand experience of the trauma of war; he models many of his works on dead bodies. Modernist artists like Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, too, produced works related to the horrors of the Revolution—even if they had not directly experienced it.

Over time the visual focus on death and dying in Mexico has transformed in response to specific socio-cultural and political changes, including epidemics, natural disasters, religious reforms, sanitation issues, political upheavals, nationalistic desires, and secularization. I believe we need to rethink how we conceive of Mexicans’ relationship to death. It is not solely a morbid fascination with what happens after life, but a way in which to navigate life more successfully.

[1] Claudio Lomnitz, Death and the Idea of Mexico (Brooklyn: Zone Books, 2005), 23.

[2] Beatriz de la Fuente and Louise Noelle, Arte funerario. Coloquio internacional de historia del arte (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1980). Other important texts include the volume Iconografia Mexicana V: Vida, muerte y transfiguración, ed. Beatriz Barba de Piña Chan (Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2004); and Nigel Llewellyn, Art of Death: Visual Culture in the English Death Ritual, c. 1500-1800 (London: Reaktion, 1997).

[3] Philippe Ariès, Images of Man and Death (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985); Death and Dying in Colonial Spanish America, edited by Martina Will de Chaparro and Miruna Achim (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2011); Will de Chaparro, Death and Dying in New Mexico (Albuquerque: The University of New Mexico Press, 2007); and Stanley Brandes, Skulls to the Living, Bread to the Dead: The Day of the Dead in Mexico and Beyond (Oxford: Blackwell, 2006).

[4] —Robert McCaa, “Missing Millions: The Human Cost of the Mexican Revolution.” http://www.hist.umn.edu/~rmccaa/missmill/mxrev.htm

More about the project+digital art history

To begin this project, I’ve started to collect data on those areas in Mexico that experienced high levels of death—whether due to epidemics, natural disasters, warfare, or politico-religious practices—and organizing it into centuries (basic, I know). My hope is that I will learn digital tools that will help me relate my findings to objects and imagery focused on death between 1521–c. 1920. My goal is to understand better what death-related issues are related to local artistic productions. I want to visualize this data to notice historical patterns related to death, death practices, and death-related art. I also want to showcase networks and subjects of art, as well as their ebb and flow. It might be useful, too, to connect visual data to archives and other primary source repositories online (like this one).

At this early stage of the project, it would be useful to view such patterns—if they exist—because it would help me to focus on specific case studies and analyze data in a different manner. Some of the materials that tell us about deathways no longer exist, so I am hoping that I can provide a way to help my audience visualize what these objects and materials looked like at different historical moments. Ideally, I would share this data with colleagues not only in art history, but also those who focus on Mexican culture and the general public.

Origins of the Project

I’ve been thinking about this project for 5 years. My dissertation focused on images of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in eighteenth-century New Spain. I kept finding evidence that suggested many paintings on copper of the Sacred Heart functioned as talismans to ward off plagues and epidemics. I kept searching for more concrete evidence, but I found little to help me flesh out the idea. But it kept me thinking about the intersections of epidemics, visual culture, and death. On a side note: I kept finding wonderful archival documents about bone worship, the flayed back of Christ, and nuns suckling Christ’s wounds that kept my attention on issues of death and dying.

While my research quickly turned in other directions (i.e., the visual culture of convents, the earliest self-portraits of the Spanish Americas, and body parts in general), I realized that I could develop a class around the material of death and dying. I envisioned it as a graduate seminar. So many students wanted to enroll the first semester that I offered it, that I decided to create an undergraduate course on the topic. It was and continues to be my most popular class.

Years later, and with my first book nearing publication, I decided to develop this material into a book, one that asks big questions and tries to ask thought-provoking and often open-ended questions. Much of the project has been informed by conversations with students and colleagues, who approach the material differently than I or who bring personal life experiences to bare on this material. I’ve enjoyed these moments, and my hope is that I can engage with others more publicly and collaboratively with this material.

Now I just need to learn all the tools. (Well, I guess I can settle for a few at the moment.)

I’m open to input and ideas, so if you have any please get in touch with me.

Day 1: My Project and Reflections on Digital Art History | Blood, Flesh, Bone.